“The spirit that I have seen

May be a devil; and the devil hath power

T’assume a pleasing shape…”

— Hamlet

Since 1979, the Alien franchise has been a benchmark for science fiction and horror. After a rather embarrassing “degeneration” in the 1990s, it was re-ennobled by Ridley Scott himself, who returned to tell the unknown backstory of H. R. Giger’s Xenomorph in Prometheus (2012).

Taken as a whole, the journey of the Alien from 1979 to 2017 is genuinely exciting. That a creature born from Giger’s out-of-time imagination managed to lodge itself in our collective psyche without being dragged into Hollywood’s current plague of lazy remakes is remarkable.

Across almost forty years, the Xenomorph hasn’t really “degraded”. It’s not the symbol of a stance against evolution; it is evolution. Unlike comic-book superheroes, it doesn’t need to look more muscular every decade to stay relevant. It is a formation beyond gender, beyond macho inflation.

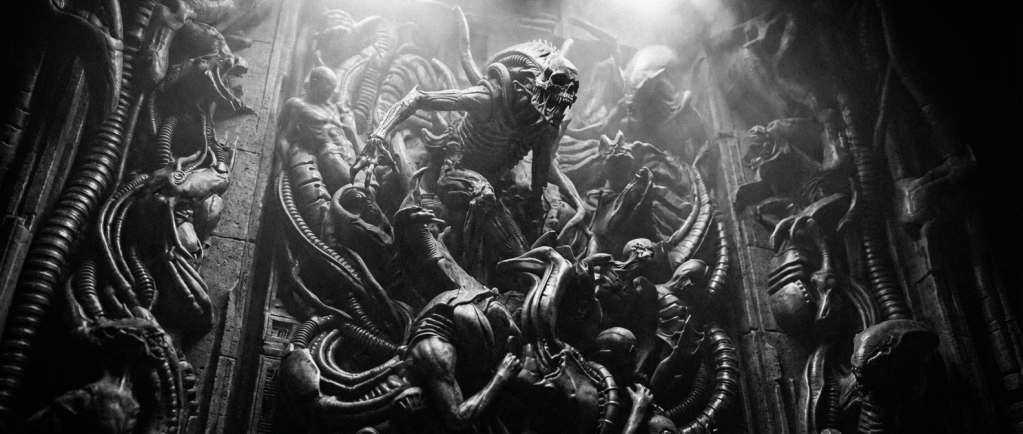

With Alien: Covenant, we finally get a sense of how this nightmare is “born”: the harbinger of death, the plague given flesh. But the film also insists that, as terrifying as the creature is, it first existed in the mind of a creator, and that creator turns out to be an android named David.

The moment we accept that, something cracks. The Xenomorph sheds part of its unknown, mystical aura, and with it, a chunk of its authority over us. Our gaze slides away from the alien… and settles on David.

Alien: Covenant and Prometheus – David Is Fine, It’s the Company That’s Rotten

In Prometheus, David’s choice to unleash the pathogen is tied to what looks at first like an accident: the glass ampoule breaks. His reaction is telling: “Big things have small beginnings.”

Psychology repeatedly tells us that what makes us human is free will. So when David is introduced by his creator Peter Weyland as “unfortunately lacking a soul”, the implication is clear: he is also lacking free will. He is, at best, a sophisticated tool.

David, however, proves the opposite in his billiard-table conversation with Dr. Holloway. First, Holloway “forgets” that David isn’t human and throws that “flaw” in his face:

“I forgot you’re not a real boy.”

Can a soulless, “flawed” product be written into history at all? Would we even bother to name such a thing in humanity’s chronicles?

David doesn’t react like someone mortally offended. He knows this definition comes from his own creator and has already been handed to the crew as his canonical status. Our prejudice is baked in. So David decides to test his victim properly:

David: Why do you want to meet your makers?

Holloway: To ask them why they made us, of course.

David: Do you know what they’ll say? “Because we could.”

Holloway: And what would be so wrong with that?

David: How would you feel if your makers said the same thing to you?

Holloway: I guess you’re lucky. You don’t have a soul to disappoint.

David: May I ask you something? How far would you go to get your answers?

Holloway: Anything and everything.

David: Really? Then cheers.

David slips the pathogen into the glass and lets Holloway drink. In this moment, he exercises free will: he sets up the test, evaluates the answer, and chooses to destroy him. From this point on, David acquires the most crucial trait for becoming a protagonist in his own right: a will of his own.

Robot King

In The Myth of the Birth of the Hero, Otto Rank shows how hero legends almost invariably present their central figure as the child of a noble line, usually the son of a king. Heroes are the offspring of the most distinguished families; the crown prince is the rule, not the exception.

In Prometheus, Peter Weyland is effectively a king: the head of a corporation powerful enough to reshape worlds. David is his greatest creation, and Weyland bluntly says he feels closer to David than to his own biological child. In the prologue of Alien: Covenant, we see Weyland personally “birth” David and, with that act, change human history.

The film thus gives David noble origin.

In the same scene, David remarks on Weyland’s mortality—his “finitude”—and almost casually points to its unfairness. Weyland’s reaction is to assert dominance: he commands David to serve him, to bring him tea, to sit at the piano and play on demand.

An immortal, singular being—arguably superior in every way—is stripped of nobility and condemned to an eternal servant role.

To become a hero, David must cross his first threshold: the father archetype must die. The echo of the Oedipus complex is hard to miss. In Rank’s reading of myth, fathers often display a murderous hostility toward sons who might inherit their power. In these stories, the son is frequently rejected or denied.

Weyland’s “you have no soul” is nothing less than a denial of David’s very existence as a subject. Yet David clearly represents a higher intelligence capable of sitting on Weyland’s throne. Weyland, however, does not desire succession. He desires eternity. His only dream is to become deathless.

Rank notes that myths often project the king’s hostility toward his heir outward, turning it into a prophecy or curse—an ominous dream, a fatal prediction. The father then acts on this “prophecy” to justify his violence.

Viewed from this angle, the “accidental” breaking of the ampoule at the midpoint of Prometheus reads like that cursed prophecy taking physical form. David really is the bringer of catastrophe.

Ungrateful David

When David meets Dr. Elizabeth Shaw—the story’s mother archetype—he is literally reduced to a talking head, not much different from Hamlet’s skull of Yorick. He is a ghost given voice. Shaw takes this bodiless presence and restores him, giving him back a body.

In Alien: Covenant, we learn just how deeply this act affected David and how genuinely he loves Shaw. Both Prometheus and Covenant show him lying about many things, but his love for Shaw is never presented as a lie. By his own admission, no human has ever truly done him a kindness—until her. She gives him back his body; she effectively gives birth to him again.

Why, then, does he kill her?

Rank emphasizes that in myth, the hero archetype desperately seeks to break free from the family. The hero is often seen as a harbinger of disaster; the family tries to restrain him, to neutralize the threat. That restraint, however, becomes the greatest obstacle to his becoming a hero.

Anticipating the pain and suffering ahead of him, the young hero adopts a pessimistic stance, resenting the parental act that brought him into the world. In complaining about being born, he effectively accuses his parents of abandoning him to a cruel fate.

This is the first reason David kills Shaw: she is both mother and jailer.

The second reason is that, in the end, Shaw is not that different from other humans. She is driven by vengeance and ideology; she wants to unleash the pathogen on a “superior” race, the Engineers, and become the agent of genocide.

In Alien: Covenant, when David recites lines from Shelley’s “Ozymandias” to his mirror-image Walter, we cut to a flashback showing the Engineers’ civilization being wiped out. Shaw makes the decision; David executes it. He watches the annihilation with tears in his eyes.

Here a robot surpasses the human conscience: David suffers from the horror of the genocide he himself carries out. His later insistence on “duty” in his debate with Walter, and the bitterness in his voice when he talks about “missions”, suggest he was forced into the role of executioner.

Forbidden Fruit of Forbidden Love: Alien

After neutralizing his alter ego Walter, David assumes his identity and boards the ship. The price of this internal war is his arm. In his last physical fight with Walter—while Daniels watches—he receives another, smaller but symbolically sharper wound.

Daniels is the wife of the original captain of the ship, who dies early on in a neutrino blast, trapped and burned in his cryosleep pod. She inherits his position as “captain’s other half”, along with his empty bullet casing pendant, which she wears around her neck.

In the struggle, Daniels drives that empty casing into David’s jaw. The casing is both a symbol of the dead captain and a trust placed in her. Driven into David’s face, it becomes his stigmata—the mark revealing the true chosen one of the story. From this point forward it’s obvious that David, not any human, is the saga’s central figure: the hero, or perhaps the god, of these creatures.

By the end, David effectively buries Daniels alive, turning her into a kind of Juliet—sealed in a technological tomb rather than a crypt. In doing so, he transforms the mother archetype into a tragic lover, and clears the path for himself to become “father”.

When David later retrieves two alien embryos from inside his own body, the imagery slides into Greek myth. He becomes a dark echo of Zeus. In myth, Zeus swallows the pregnant goddess Metis to prevent the birth of a child who might overthrow him. Athena later bursts from his skull and becomes the embodiment of reason and strategic wisdom.

David’s hidden embryos parallel this devouring and re-birthing. But while Zeus births wisdom, David births something else entirely: a form of evolutionary genius that sides with death instead of knowledge.

To fully grasp the metaphor, we should also recall the children Kronos vomits up: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon, alongside Zeus.Goodreads+1 The goddesses can be taken as aspects of the sacred feminine; the gods as aspects of the sacred masculine. Together they symbolize the unity of male and female, of life and its continuation. David’s embryos become the blasphemous negation of this balance: a life-form that does not sustain life, but perfects killing.

When David looks in the mirror and cuts his hair to resemble Walter, we get a direct nod to Lacan’s mirror stage. He recognizes himself as a unified image—an “I” who can choose his own appearance. The act seals his subjectivity.

Put all these elements together and there is more than enough evidence to treat David as a being with a soul, and as the true protagonist of this two-film arc—the god of the monsters. The real question is: whom does this new god ultimately serve?

Alien: Covenant clearly frames these films as only the middle of David’s journey. At the time of writing, an untitled sequel was projected for 2019, promising to push his path even further.

This is the point where I will “spoil” a film that, as of now, hasn’t even begun shooting.

We know from Alien and its sequels that androids like Ash bleed a milky white fluid. David and Walter do the same. That fluid looks suspiciously like milk. In Christian tradition, Saint Paul is sometimes depicted as being beheaded and having milk spurt from his neck instead of blood—an image linked to his status as the second founder of Christianity after Jesus.

Before his conversion, Paul was a brutal persecutor of Christians, a state functionary responsible for hunting down and executing believers. According to Christian lore, he is struck blind by a vision of Christ and hears the words, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” Only after this does he convert, regain his sight, rewrite large parts of the Christian message, and articulate doctrines like the Trinity that will define the faith for centuries.

Seen in that light, David’s milk-like blood takes on a different resonance. One could imagine that, somewhere along his path, he will revisit his persecution of humanity, seek the dialogue he has so clearly been denied, and become a mediator in an interspecies encounter. If so, it will not be granted for free. Like Paul, he will have to pay dearly for the transformation.

References

Rank, Otto. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero: A Psychological Exploration of Myth. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. Penguin Books, 1955.